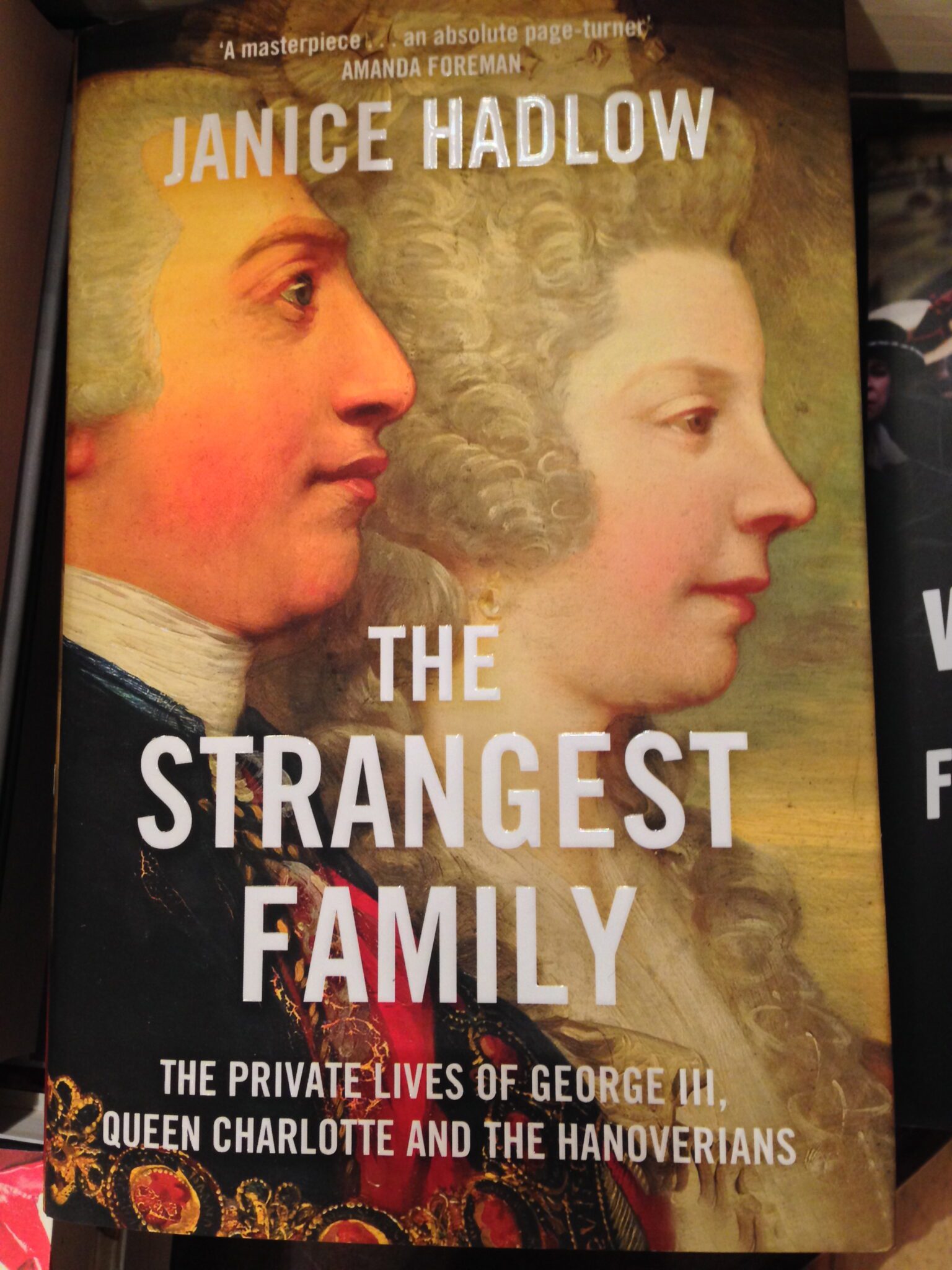

The Strangest Family by Janice Hadlow (Book Review)

I love history. I like stories and I am interested in people, and the two seem to perfectly come together when reading history. Although I’ve read a lot of books about the Tudor, Stuart and Victorian era, the Georgian period hasn’t really caught my attention until recently. The play/movie ‘The Madness of King George’ has sparked my interest in the 18th century social history — the story of the people of Jane Austen’s novels, who watched as revolutions raged on the continent and who lived through enormous political, industrial, economic and social change.

The Strangest Family is, above all, a meticulously researched and enjoyable book, designed to give the reader a panoramic view of the Hanoverians. Although the focus is on George III and his family, the inclusion of a lengthy account of the family roots, going back to George I, is a fascinating background to understanding the world of the Hanoverians. As Hadlow indicated by the title of her book, the Hanoverians were an odd bunch. George III’s great-grandfather, the Elector of Hanover who was crowned as George I in 1714, was an incredibly ruthless man — had numerous mistresses and drove his wife Sophia into the arms of another man. George’s reaction to his wife’s infidelity was merciless: he had the man murdered and his wife imprisoned in a remote castle in Germany never to see her children again. After banishing his wife, her portraits were stripped from the walls of the royal palaces, and his anger was transferred to his oldest son, the future George II, and his daughter-in law Caroline. He took hold of their children, banned them from the royal palaces and persecuted them endlessly until his death. Although George and Caroline had a close relationship, when he ascended to the throne he became just like his own father: took on many mistresses and had a rough relationship with his oldest son. His relationship with the Prince of Wales was terribly bad that when his son suddenly died of pneumonia at age 43 he proudly declared, “I have lost my oldest son and I am glad of it.”

Having witnessed three generations of infidelity, father-son hating each other as well as other tragic family events, George III ascended to the throne determined to be an entirely new kind of king. Unlike his forebears, he was determined to live a life of ‘high moral standards’ as a role model to his subjects. He resolved ‘none of the womanising or keeping mistresses and all of that mess’ that the men in his own family had done. He reinvented the concept of the ‘Royal Family’ and as the author points out, his policies continue to be followed by our own monarchs today. Although besotted by an English beauty named Sarah Lennox, George III has chosen to marry a Protestant princess from Germany, Charlotte of Mecklenburg.

Hadlow hasn’t examined the king’s political role but only highlighted some significant events of George III’s reign like the American war and the French revolution. The main focus was on the king’s family life with emphasis on George and Charlotte’s very fascinating and complex relationship with their many children. Although George was a very doting father, often seen playing with his children and even sitting on the floor while playing with his daughters, Charlotte was constantly pregnant for the first 21 years of their marriage. In 1780 she wrote: “I don’t think a prisoner could wish more ardently for his liberty than I wish to be rid of my burden and see the end of my campaign. I would be happy if I knew this was the last time.”

The royal couple shared the pain of losing their two small children: 2 year-old Alfred died in 1782, and 4 year-old Octavius in 1783, after a smallpox vaccination. It’s tragically described in detail. And then the death of their youngest daughter Amelia, at 21, who was George’s favourite, was believed to be the final blow to the King’s rapid fall into insanity. His mental illness had a profound impact on his family, and there’s a story of the princesses even sleeping in the Queen’s bedroom to guard their mother from the King’s rage and other unpredictable behaviour.

It’s very painful to read stories of the princesses imprisoned (for lack of a better word) at the royal palaces and have absolutely no freedom to make any decision for themselves. Each of the princesses has a very fascinating story. One of them, Sophia, had rebelled against her parents and became pregnant by one of the equerries (and these are the only men that the princesses ever saw) but she had to give up her child. The father, Colonel Garth, took the baby and the poor child grew up not knowing his own biological mother. There’s a heart-wrenching account of Princess Sophia agonisingly watching her own son playing at the Weymouth beach every summer, and she couldn’t even acknowledge him for fear of getting her little secret out.

While the princes were given some freedom like being sent to train in the Navy at an early age, the princesses were trapped at home and were treated like little children even in adulthood. It was heartbreaking to read detailed stories about the princesses suffering from stifling boredom and frustration. They all wanted to be married but couldn’t. They all found out later on how many proposal their father had rejected. The princesses tried to get their brother, the Prince Regent, to convince their father to allow them to set up house on their own. If getting their own freedom only means moving out of their parents’ prying eyes then they were very happy to do so. But then the king in his desire to dictate to his children’s future, convinced the Parliament to issue Royal Marriages Act of 1772, which prevented his own children from marrying without his permission. It was unbearably sad that the daughters had to wait until their father was mad for them to attain the very freedom that was denied to them.

This book tells a heartbreaking detailed story of a dysfunctional family who tried to live up to what they call a ‘high moral standards’ but at the same time struggling to overcome their own unconventional upbringing. It also illustrates the birth of the tabloid press with the papers reporting little stories about “The King indulging in ‘sea-bathing’ in Weymouth beach” and other private affairs of the royal family. I must conclude (and Hadlow didn’t make any mention of Victoria and other descendants of George) that if King George III had failed to make his family the moral compass for the nation, it was his granddaughter, Queen Victoria, who continued the model of domestic virtue that her grandfather had tried to do. Excellent biography full of intriguing stories, and I couldn’t put the book down, reading the 600-pages book in less than a week.

This book tells a heartbreaking detailed story of a dysfunctional family who tried to live up to what they call a ‘high moral standards’ but at the same time struggling to overcome their own unconventional upbringing. It also illustrates the birth of the tabloid press with the papers reporting little stories about “The King indulging in ‘sea-bathing’ in Weymouth beach” and other private affairs of the royal family. I must conclude (and Hadlow didn’t make any mention of Victoria and other descendants of George) that if King George III had failed to make his family the moral compass for the nation, it was his granddaughter, Queen Victoria, who continued the model of domestic virtue that her grandfather had tried to do. Excellent biography full of intriguing stories, and I couldn’t put the book down, reading the 600-pages book in less than a week.

(Cover photo: Royal Collection. King George III, Queen Charlotte with 13 of their 15 children.)