The Bank of England Museum

In January I came up with a list of museums and galleries I wanted to visit this year, some of them I’ve already visited in the past but others haven’t. Over three weeks ago we visited The Bank of England Museum and after posting a picture on Instagram and Facebook, a lot of my friends were surprised that such a museum exists. I had no idea that not very many people, even local residents, are aware that The Bank of England has a museum. Although not very large, the museum is laid out in such a way that it leads the visitors through the narrow corridors and rooms and takes them on a journey through the history of the bank. I found it so interesting, and yes, fun as well.

The museum is housed in a beautiful building designed by the bank’s architect from 1788 to 1833, Sir John Soane. The original building was almost completely demolished in the 1920s except for the curtain wall around the outside of the bank. The building was rebuilt by Sir Herbert Baker in order to expand the premises. Upon entering the museum, there’s a small shop on the right side and in the middle of the dome structure is an interactive boat game you can go through and play around: set monetary policy to control inflation and navigate through the history of financial storms from the 17th century to the present day.

Upon entering the museum, there’s a small shop on the right side and in the middle of the dome structure is an interactive boat game you can go through and play around: set monetary policy to control inflation and navigate through the history of financial storms from the 17th century to the present day.

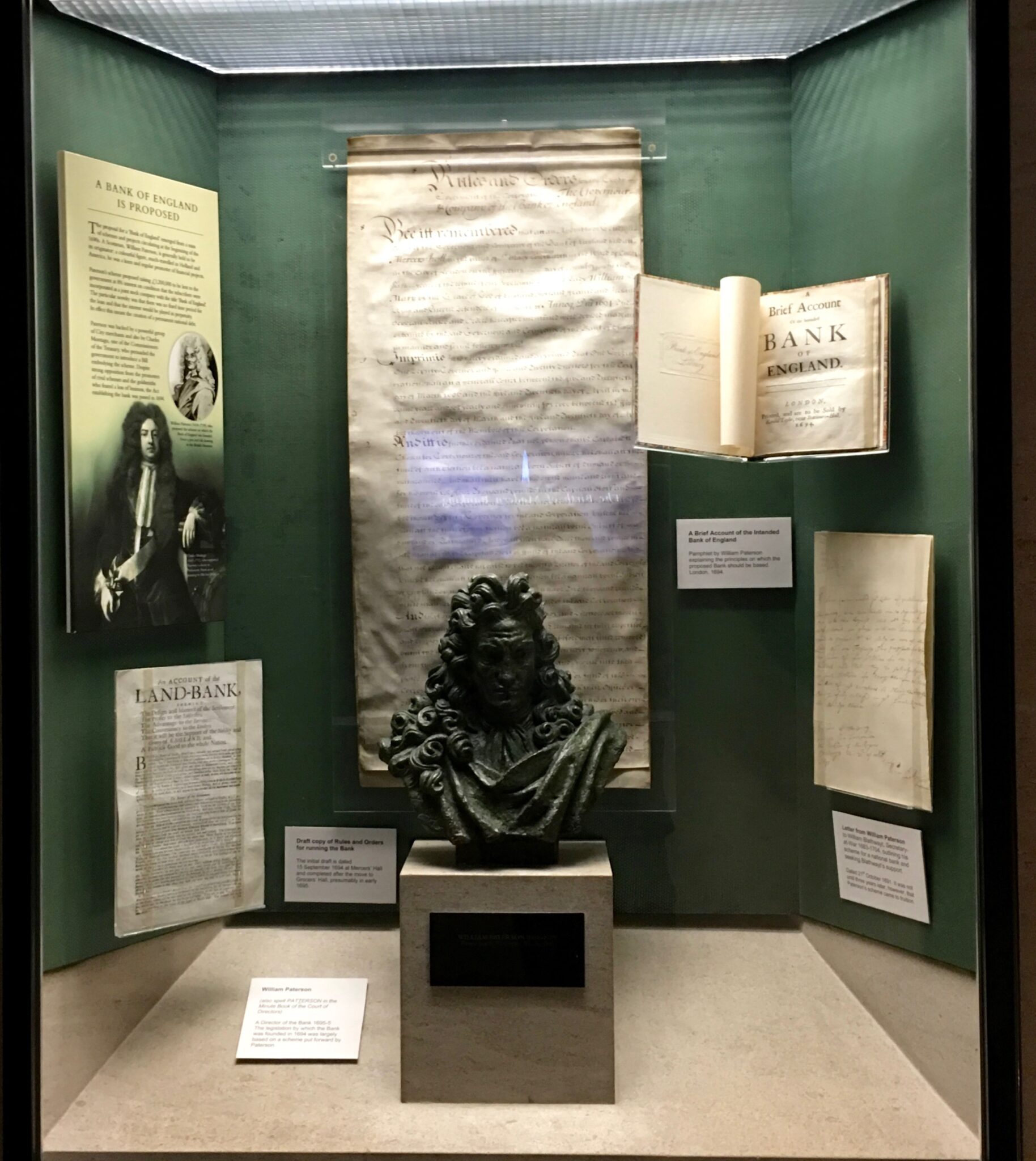

Then the virtual tour follows tracing the history of the Bank from its foundation in 1694. An architect’s blue print of the first building in Threadneedle Street is on display, and The Bank of England claims that it was the very first purpose-built bank in the world. I had no idea before visiting the museum that banking in England effectively evolved from the goldsmiths’ role as bankers: that is, the essential functions of deposit and lending and issuance of note. Apparently, the merchants and wealthy individuals would deposit their cash and valuables for safekeeping, and the goldsmiths would then keep the money with them and paid interest on it. The money could then be used productively by lending them out at interest to merchants who needed capital. A handwritten receipt or “goldsmith’s note” is then issued to the depositor which represented a promise to pay him back his deposit. It became the forerunner of the modern bank note.

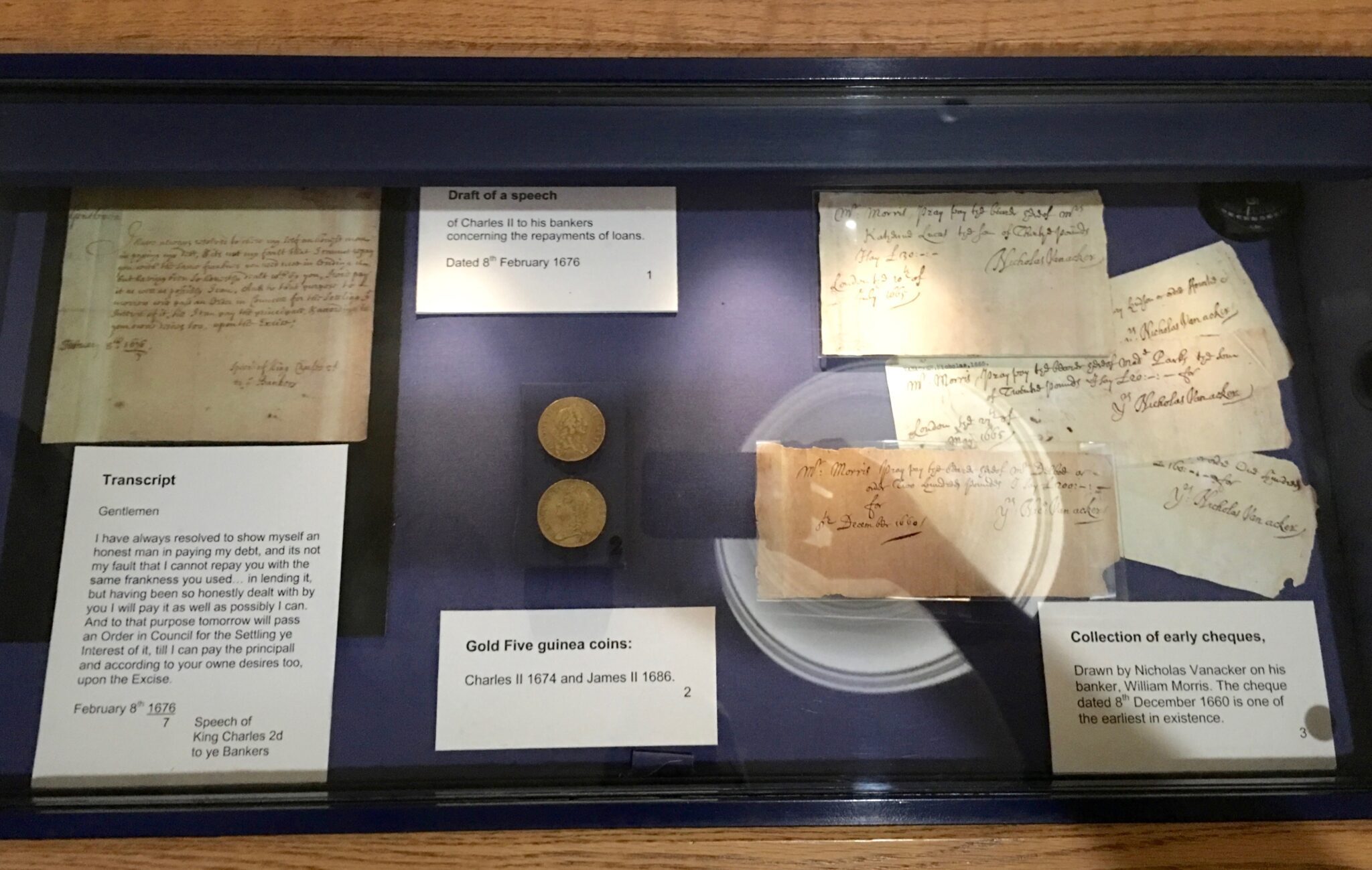

The place is designed so the visitors are led through the museum in such a way that they don’t miss anything. Original copies of handwritten “goldsmith’s note” and “early cheques” are on display, and although the handwriting is very difficult to understand, it actually is pretty cool to see those 17th century notes.

The place is designed so the visitors are led through the museum in such a way that they don’t miss anything. Original copies of handwritten “goldsmith’s note” and “early cheques” are on display, and although the handwriting is very difficult to understand, it actually is pretty cool to see those 17th century notes.

The visitors can also see the gold and silver coins during the reign of William and Mary.

The visitors can also see the gold and silver coins during the reign of William and Mary.

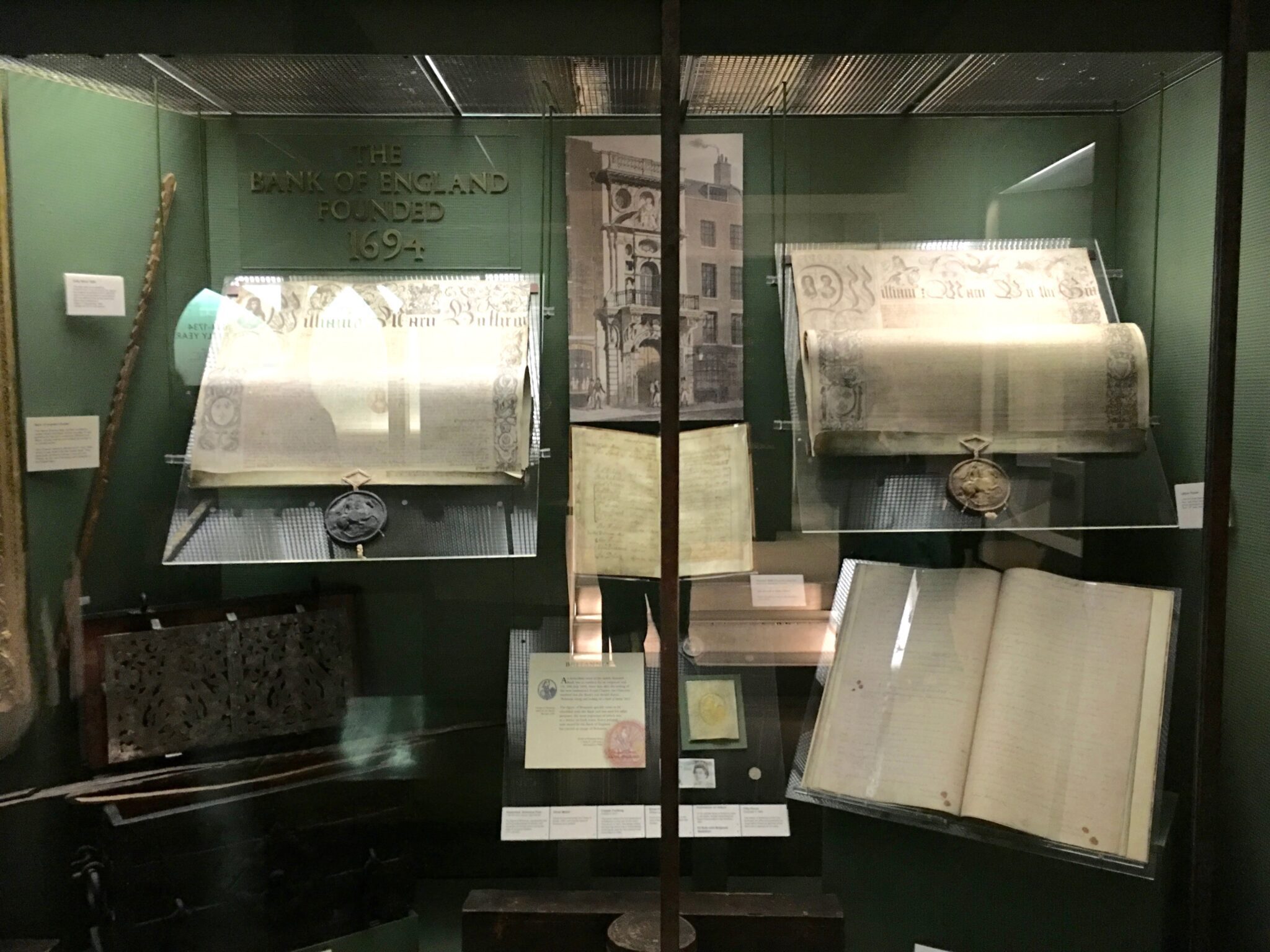

The Original Royal Charter shows why the Bank was founded in 1694.

The Original Royal Charter shows why the Bank was founded in 1694.

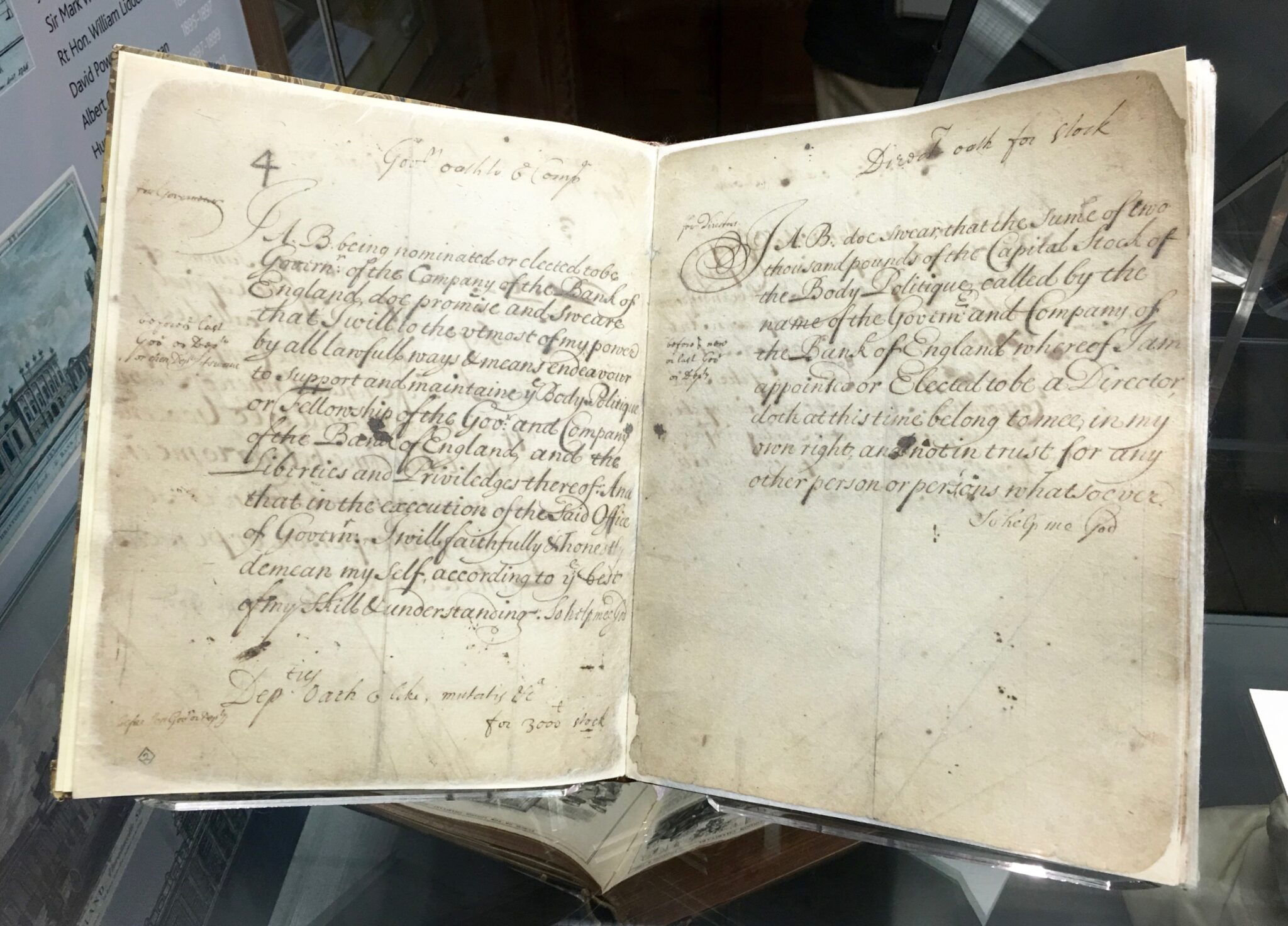

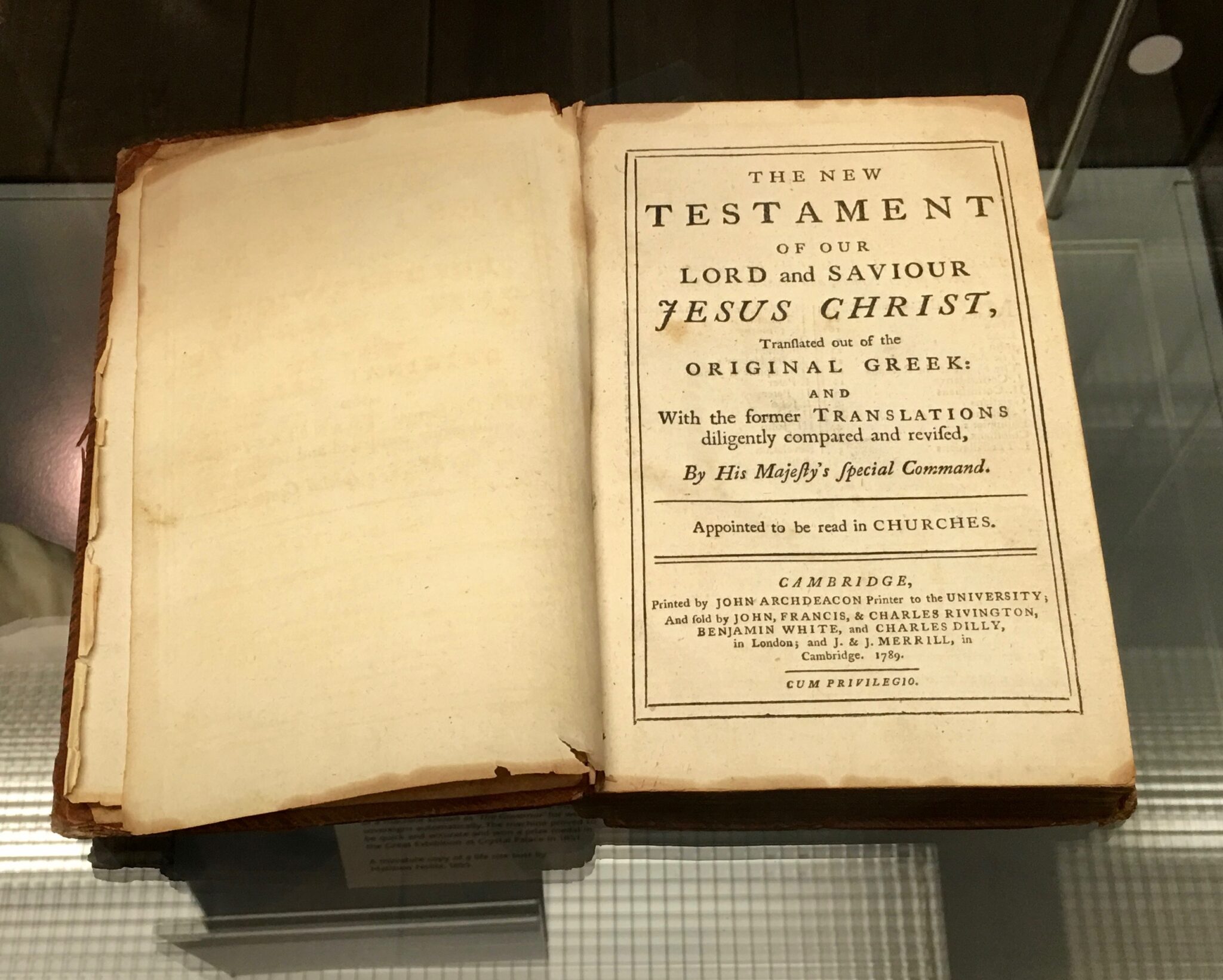

They have a lot of interesting objects such as the Iron Chest, Book of Oath, Bible, and many more.

They have a lot of interesting objects such as the Iron Chest, Book of Oath, Bible, and many more.

This Book contains the texts of Oath by the Governors of the Bank in which they declare before taking office that they will.. “by all lawful ways and means endeavour to support and maintain the Bank of England…”

This Bible on which the ‘oath’ is made.

This Bible on which the ‘oath’ is made.

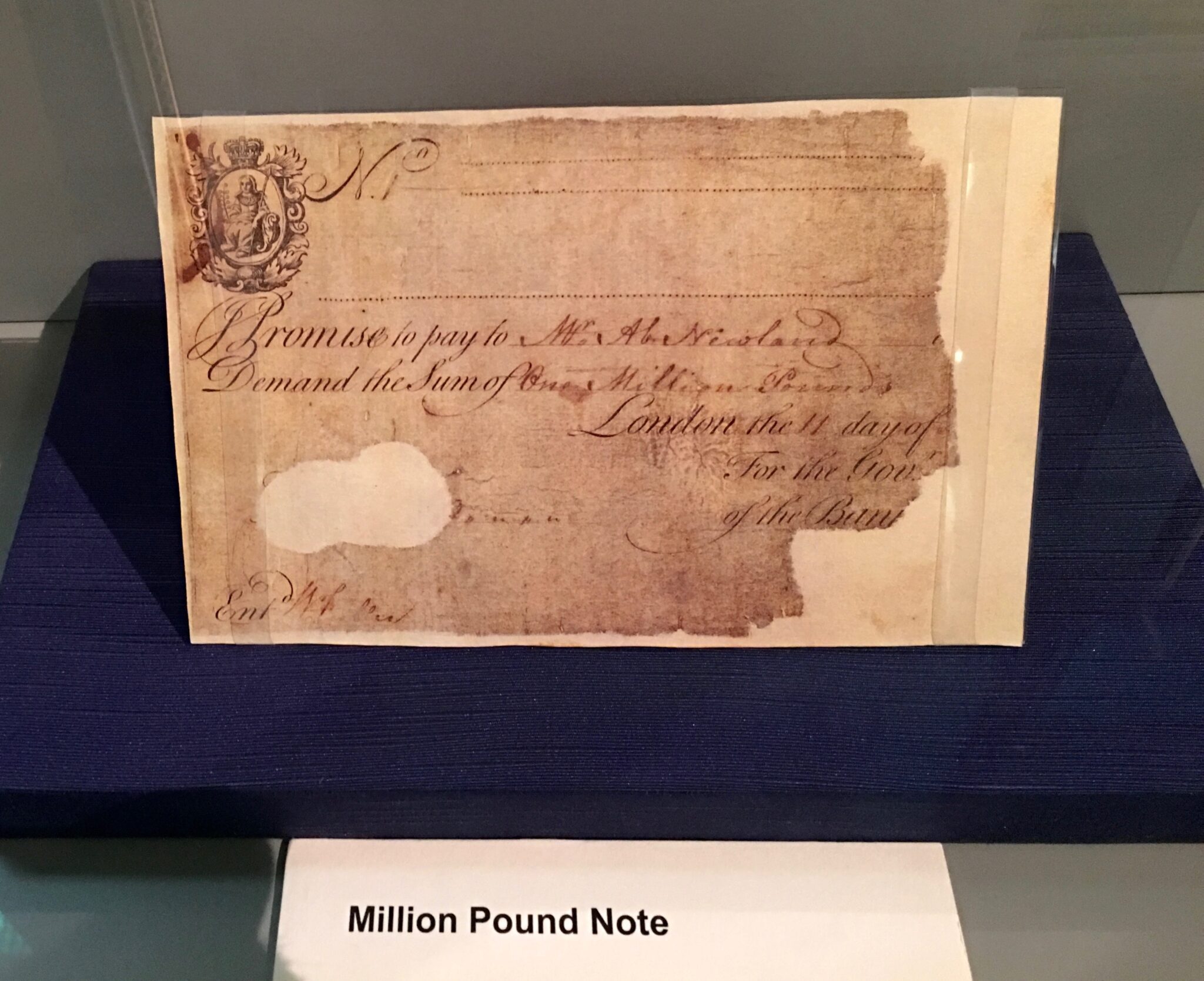

Interestingly, £1 million notes like this picture below was used by the Bank for internal accounting during the 18th century. Nowadays they use £100 million notes for the same purpose.

Interestingly, £1 million notes like this picture below was used by the Bank for internal accounting during the 18th century. Nowadays they use £100 million notes for the same purpose.

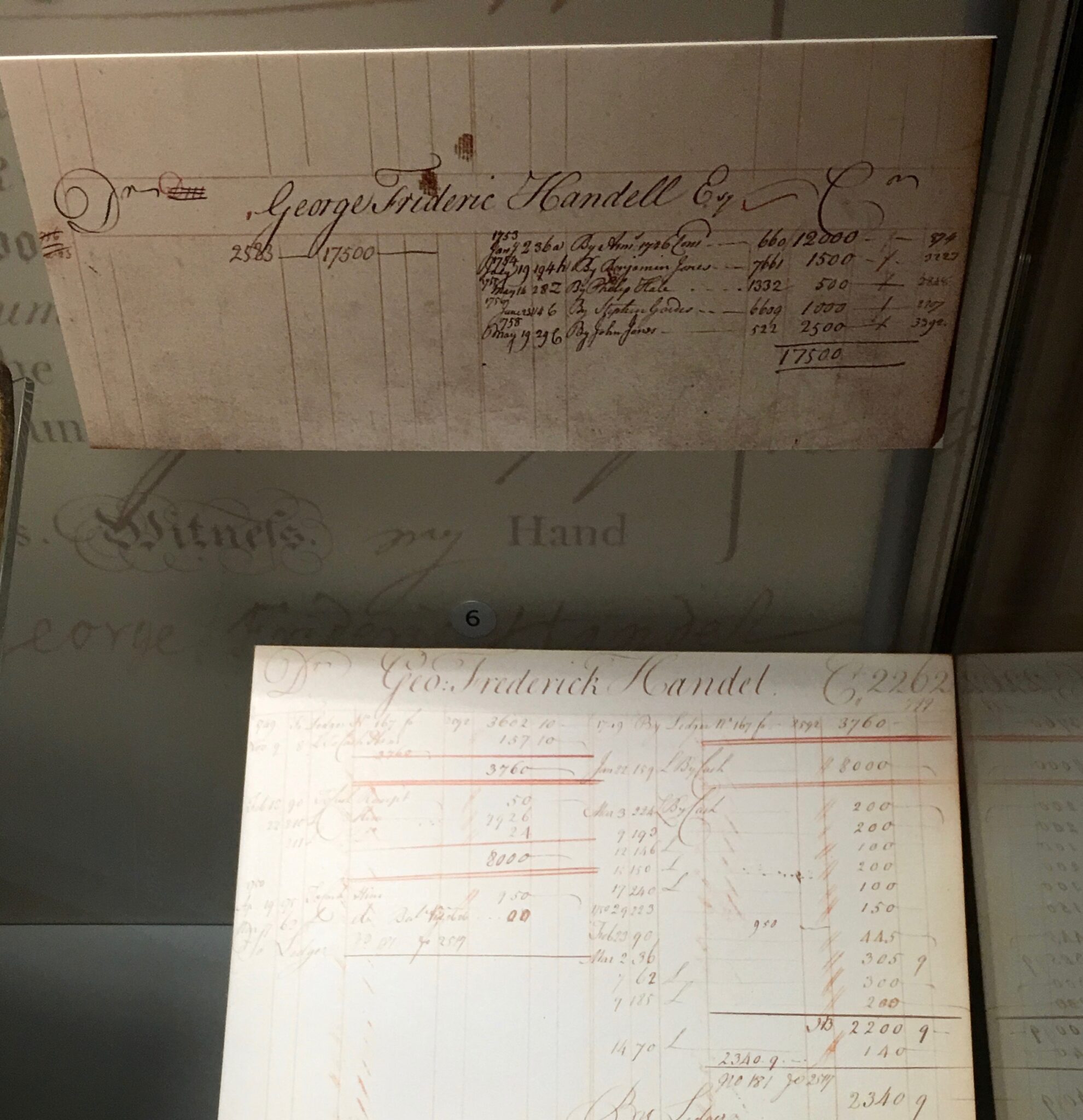

George Frederick Handel, one of the best known Baroque composer, settled in London in 1710 until his death in 1759, held two accounts at the Bank of England: ‘Drawing Account’ the equivalent of today’s ordinary current account and a ‘Stock Account’ which he used to invest prudently in the Government Securities managed by the Bank.

George Frederick Handel, one of the best known Baroque composer, settled in London in 1710 until his death in 1759, held two accounts at the Bank of England: ‘Drawing Account’ the equivalent of today’s ordinary current account and a ‘Stock Account’ which he used to invest prudently in the Government Securities managed by the Bank.

One of the highlights is the interactive display and the life sized moving models of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger (he’s called as such to distinguish him from his father, William Pitt the Elder) and Charles Fox, Britain’s first Foreign Secretary, re-enacting their famous debate in the House of Commons over monetary disciplines. Fox argues that every note issued by the Bank should be backed by gold. Pitt, on the other hand maintains that the Bank should issue as many notes as needed. The Government Monetary indiscipline during this period (1797-1821) was already contributing to worryingly high levels of inflation.

The Bank Note Gallery has some very interesting displays on how the ‘gold standard’ gradually became English monetary system in the 18th century and how it was adopted by most of the world’s major trading nations such as Germany, Japan, Russia and the United States.

The most popular display is a real bar of gold which the visitors are allowed to try and pick up with one hand.

Many of the exhibits takes the visitors to the displayed coins and notes that’s long been out of circulation.

Many of the exhibits takes the visitors to the displayed coins and notes that’s long been out of circulation.

For hundreds of years before decimalisation, British pound sterling used an old system that could be traced back to pre Anglo-Saxon times. Up until the 14th of February 1970, there were twelve pennies in a shilling, and twenty shillings in a pound. Confusing as the old system must have been, people in Britain back then must be very good at mathematics. 🙂 I am just so glad I no longer have to worry about it. 😉 Today it’s more simple: a pound is made up of a hundred pence.

For hundreds of years before decimalisation, British pound sterling used an old system that could be traced back to pre Anglo-Saxon times. Up until the 14th of February 1970, there were twelve pennies in a shilling, and twenty shillings in a pound. Confusing as the old system must have been, people in Britain back then must be very good at mathematics. 🙂 I am just so glad I no longer have to worry about it. 😉 Today it’s more simple: a pound is made up of a hundred pence.

I learned while visiting the museum that The Bank of England has nine vaults located beneath the City of London, and covers a floor space greater than Tower 42, the second-tallest building in the city. Gold bars are stacked on warehouse-like shelves like giant Toblerones on display in a supermarket. That’s where the Bank stores more or less £200 billion worth of gold bars. But the only way to get inside is with a key that is 90 cm long. And of course, you have to know someone (names of those who have access are kept secret) if you want to have a look inside one of the basement vaults.

I learned while visiting the museum that The Bank of England has nine vaults located beneath the City of London, and covers a floor space greater than Tower 42, the second-tallest building in the city. Gold bars are stacked on warehouse-like shelves like giant Toblerones on display in a supermarket. That’s where the Bank stores more or less £200 billion worth of gold bars. But the only way to get inside is with a key that is 90 cm long. And of course, you have to know someone (names of those who have access are kept secret) if you want to have a look inside one of the basement vaults.

The museum is designed to appeal not just to the bankers and the economists but to a much larger audience, ordinary people like myself who is not in the financial sector. It is a self-tour and free of charge, and offers the visitors to take their time to walk around and see everything at their own pace. Before the visit, I never thought that a museum about money would be that fascinating and fun. I thoroughly enjoyed the visit and couldn’t recommend it highly enough. Well worth a visit not just for anyone visiting London but even the local residents who are not interested in the history of the British Pound Sterling.