Remembrance Poppy: Keep the Memory Alive

When I relocated to London fifteen years ago, I noticed that a lot of people, especially the elderly, had a red poppy pinned on their chest on Memorial Sunday. I followed the tradition without giving much thought to the profound meaning before sticking it dutifully on my chest. Until thirteen years ago, when I was stopped by an old military man selling poppies at High Street Kensington, and asked if he could reposition the poppy on my coat. I had it on my left chest so he told me that women should wear their poppy on their right side. He went on to explain the meaning of each colours: the red represents the blood of all those who gave their lives; the black represents the mourning of those who had their loved ones killed during the battle; and the green leaf represents the grass and crops growing and the future peace and prosperity after the war. The leaf, according to the old gentleman, should be positioned at 11 o’clock to represent the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the exact time that First World War formally ended. After he’s done explaining all of these, he took a deep breath and said, “I fought in the Second World War, and I’m afraid the younger generations have got no interest in history especially about the Great War and our generation wouldn’t be around for much longer to teach them.” It was such a lovely chat I had with him, and I walked away feeling terribly ashamed of myself that I didn’t even know that each colour of the paper poppies I had on my lapel have meaning attached to it. It was an experience I’d never forget.

So how did the remarkable red flower become such a powerful symbol of our remembrance of the sacrifices made in past wars? After that brief encounter with the old veteran at High St Kensington, I tried to educate myself on war history by reading up books on The Great War. I learned that the poppy’s origin as a popular symbol of remembrance lies in the landscapes of the First World War. Apparently, scarlet corn poppies grow naturally in conditions of disturbed earth throughout Western Europe. The destruction brought by the Napoleonic wars of the early 19th century transformed bare land into fields of blood red poppies, growing around the bodies of the fallen soldiers. In late 1914, the fields of Northern France and Flanders were once again ripped open as First World War raged through Europe. Once the conflict was over the poppy was one of the only plants to grow on the otherwise barren battlefields.

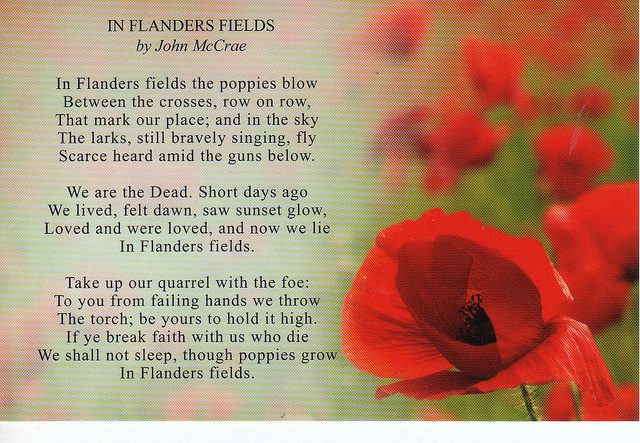

Poppies were a common sight, especially on the Western Front, according to the war history books I’ve read, and they flourished in the soil churned up by the fighting and shelling. The flower provided Canadian surgeon Major John McCrae with inspiration for his poem ‘In Flanders Fields’, which he wrote while serving in Ypres (an informal name given to a series of battles in northern France and southern Belgium) in 1915. It was first published in Punch, having been rejected by The Spectator. In 1918, in response to McCrae’s poem, American professor and author Moina Michael wrote ‘And now the Torch and Poppy Red, we wear in honor of our dead…’. She campaigned to make the poppy a symbol of remembrance of those who had died in the war. Eventually the poppy came to represent the unfathomable sacrifice made by the men and women in the armed forces and quickly became a lasting memorial to those who died in the First World War and later conflicts. It was adopted by The Royal British Legion as the symbol for their Poppy Appeal, in aid of those serving in the British Armed Forces, after its formation in 1921.

Artificial poppies were first sold in Britain in 1921 to raise money for the Earl Haig Fund in support of ex-servicemen and the families of those who had died in the conflict. They were supplied by Anna Guérin, who started manufacturing the flowers in France to raise money for war orphans. Selling poppies proved so popular that in 1922 the British Legion established a factory, staffed by disabled ex-servicemen, to produce its own. It continues to do so today. The poppy continues to be sold worldwide to raise money and to remember those who lost their lives not just during the First World War but also in subsequent conflicts.

I noticed in the last few years that it has become almost a political protest not to wear a poppy these days. When you’re walking down the street almost every person you see has a red poppy on their lapel. Even on tv, the red poppy is pinned to every person on screen, from the morning talk show hosts and news reporters to sport commentators. I feel that there is something terribly wrong with enforced display of patriotism when people don’t even appreciate their heritage, much less know their own history.

What is ironic is the fact that this country has hypocritically embraced socialism, the very thing it has fought against and defeated in the Second World War. Today the damage caused by socialism is clearly seen in all aspects of the British society. All politicians, Socialists and Tories alike, aspire to the same classless ideal. The system which we now live under is very much like Hitler’s socialist regime where freedom is slowly but surely being taken away from the people. And what is currently happening is a poignant reminder that this country is continually going down the path of extreme secularism and socialism. It’s a sad reality indeed. But the Lord knows it all. May be one day this country will once again embrace its Christian heritage but until then, we, the Christians who live in this country, have to constantly remind ourselves that everything is passing and temporal; that we are just pilgrims and strangers in this world. One of my favourite biblical passages says, “Be still, and know that I am God: I will be exalted among the heathen, I will be exalted in the earth.” (Psalm 46:10, KJV)