Handel’s House Museum

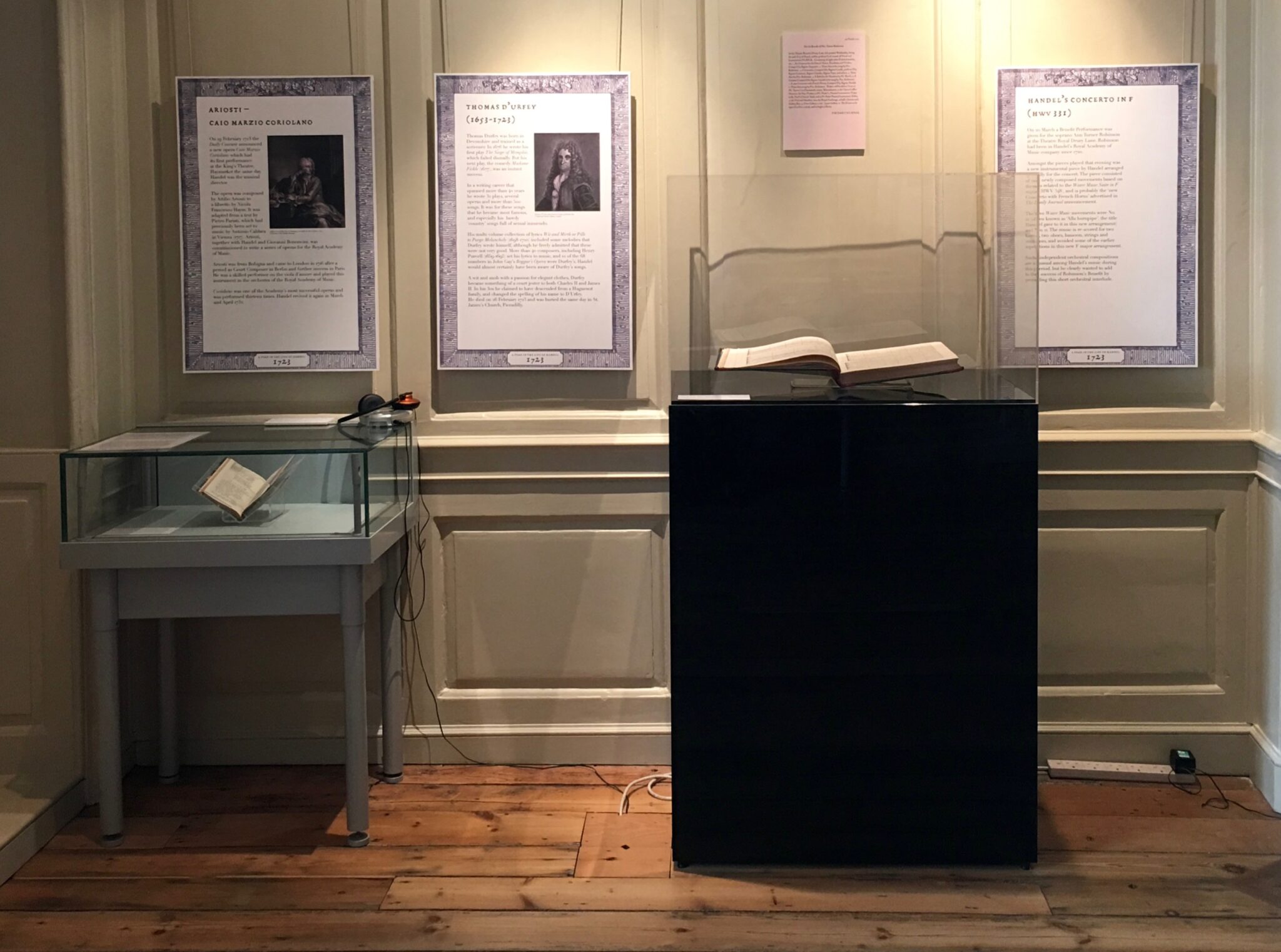

We visited Handel’s House Museum for the first time a couple of weeks ago prior to watching the Messiah at the Royal Albert Hall. The house looks pretty much like it would have been in Handel’s day with some period furnitures that’s either donated and/or loaned to the museum by the V&A Museum, Royal Collection and other patrons. The very first thing that caught my attention as soon as we walked into the first room called the ‘composing room’ was the creaky wooden floorboards. Everywhere we walked around the house the floorboards did make a squeaky sound hence, on our way out I asked one of the staff to inquire if they had carpets around the house when Handel lived there, and she told to me that back then the streets were muddy so they would have put straw mats and not some fancy carpets on the floor.

There was no audio guide but there’s are volunteer staff walking around the house and the visitors can ask them questions about anything. They seem to know a lot about the history of the house and the life of the renowned composer. There are also information boards on the walls and plastic cards on top of the table in each room that explain in detail the photographs, furnitures and other objects around the house.

Right now there’s five rooms that the visitors can explore: the composing room, rehearsal room, his bedroom, dressing room and an exhibition space.

Adjacent to the composing room is the rehearsal room. This would have been the space in the house where Handel kept his harpsichord and other musical instruments, and rehearsals would have occurred in this room as well. As it’s the biggest room in the house, this is probably where Handel also entertained his guests, some of them were the most prominent figures of the Georgian age.

The second floor contained Handel’s bedroom in the front, facing Brook Street, and the dressing room at the back.

This 1730s dressing table was loaned to the Handel House Trust by the V&A Museum.

In 1717 Handel composed Water Music and it was performed in July of the same year more than three times on the The Thames River for the King and his guests.

In 1717 Handel composed Water Music and it was performed in July of the same year more than three times on the The Thames River for the King and his guests.

Framed photographs of some of the most prominent figures (mostly opera singers and musicians) of the day are hanging on the walls. They’re all friends of Handel and have visited him at his house.

Framed photographs of some of the most prominent figures (mostly opera singers and musicians) of the day are hanging on the walls. They’re all friends of Handel and have visited him at his house.

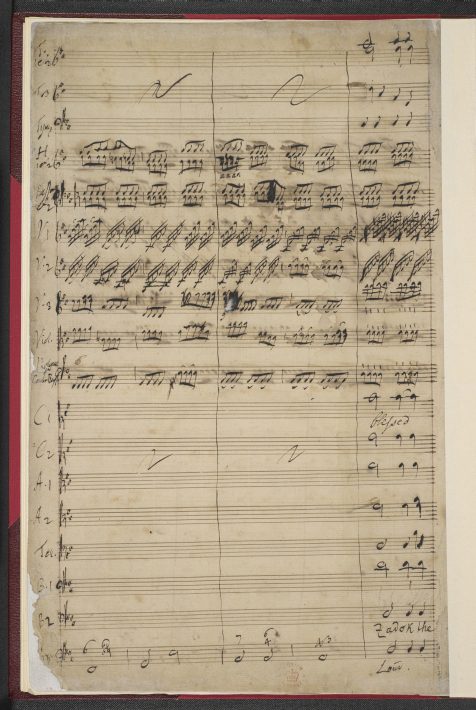

In 1727, Handel composed the four Coronation Anthems including the ‘Zadok the Priest’ for King George II, and it has been sung at every British coronation since then. The original manuscripts of all four coronation anthems are preserved in the British Library.

In 1727, Handel composed the four Coronation Anthems including the ‘Zadok the Priest’ for King George II, and it has been sung at every British coronation since then. The original manuscripts of all four coronation anthems are preserved in the British Library.

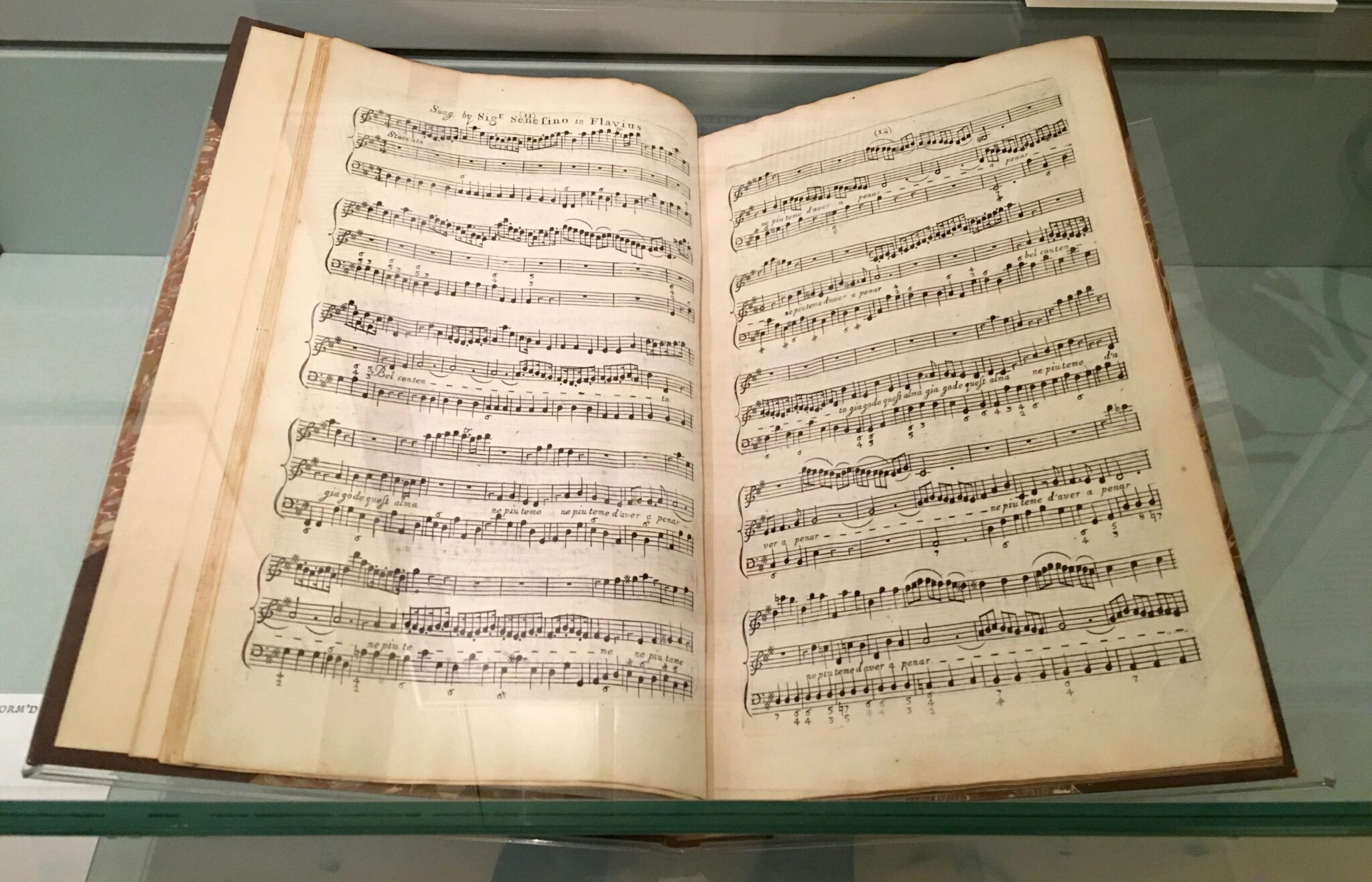

There’s a few music scores you can see around the house but don’t expect to see any of Handel’s personal possessions. I would have liked to have seen a kitchen with a roaring fireplace, chunks of meat, bread, etc., on top of a table. I mean, a little ‘Georgian-style’ kitchen would certainly bring a bit of life to the place (like they do in the John Wesley’s House Museum). The only room that is properly furnished is his bedroom at the top floor, which has a plush red bed, a chamber pot and a dressing table. Don’t go there expecting to see how Handel lived because you’ll certainly be disappointed.

So how did a world-renowned German composer end up in London, you ask?

So how did a world-renowned German composer end up in London, you ask?

Well, let me now turn my attention to his life from the time he moved to England until his death. I’ve read the book, “George Frideric Handel: A Music Lover’s Guide to His Life, His Faith & the Development of Messiah and His Other Oratorios.” I will summarise what I learned from the book.

After musical studies in Germany and Italy, Handel became Kapellmeister (composer of the music at a chapel) for a German prince named Elector Georg Ludwig of Hanover (great-grandson of King James I), who was crowned King George I of England and Scotland in 1714 (he succeeded his distant cousin Queen Anne who died without an heir). In 1712 Handel permanently settled in England after getting a £200 annual income from Queen Anne for a music he composed for her. As Handel already knew the Hanoverians prior to his relocation to England, the new king and his family had become his greatest supporter. The king, queen and other senior members of the royal family would always show up at Handel’s opera and oratorios at least twice or sometimes three times in a week. In 1722 Handel received a royal appointment as a composer to the Chapel Royal, and with his increasing popularity and financial stability, he moved into a modest London townhouse, and remained there until his death on 14th April 1759. It was in this house that he was to create some of his most important and popular works.

The house wasn’t very big but newly-built when Handel moved in. And he didn’t need a big place; he never married so it was practically a bachelor’s pad just enough for himself and a servant or two. He’s chosen Brook Street because it was close to St. James’s Palace where he has to report for his royal duties, and also near King’s Theatre in Haymarket where he staged most of his operas. Before relocating to Brook Street, he lived in several houses of his wealthy patrons.

By 1723 Handel was already at the centre of London’s cultural life, and aside from being the composer of the Chapel Royal, he was also appointed by King George I as a tutor to his granddaughters, the three royal princesses: Anne (aged 13), Amelia (11), and Caroline (9), daughters of the Prince of Wales, the future George II, and Caroline of Ansbach — the couple who had been banished from court while their children stayed with their grandparents. (please read more about the Hanoverian family saga in my previous post).

Handel’s greatest passion was for the Italian opera and in the 1730s it was quickly falling out of fashion in England. But still, Handel continued to write operas into the 1740s, losing more money and getting into enormous amount of debt. His friends expressed their concern that the concert hall was most of the time nearly empty. “Never mind,” Handel would simply joke, “an empty venue would mean great acoustics.” By 1737 Handel seemed like a big failure. Although having the King, the Prince of Wales and other members of the royal family as his supporters, his opera company went bankrupt. On April 13th 1737, he collapsed and suffered from what his doctors call a “paralytic stroke” and “of a permanent nature.” However, Handel had worked himself almost to death trying to recuperate and he eventually regained his power to walk again. To the London high-society, it seemed as if this ‘German nincompoop‘ (foolish/stupid person) as he was once called, was finished.

He decided to travel back to Germany one day and entered Aix-la-Chapelle to play the organ with his left hand but he suddenly found strength on his right hand as he moves along the keys. The cathedral was then flooded with music. Handel bowed his head and said, “I have come back from Hades.” He went back to London, still in great physical pain and being chased by creditors, Handel eventually fell into a black depression and contemplated a suicide. To make matter worse, his oratorio (a concert piece with a choir, soloists, an ensemble, and no props or elaborate costumes), became controversial and was met with outrage by the Church of England. His first oratorio, and actually the very first of its kind in English, Esther, was condemned. “The words of God were being spoken in the theater!” was the protest of the church. “What are we coming to when the will of Satan is imposed upon us in this fashion?” cried one minister of the Church of England. The Bishop of London prohibited Handel’s oratorio from being performed. But Handel proceeded anyway, and when the royal family attended, it was met with success. But the church was still angry despite the royal family supporting Handel and his oratorio.

One night Handel walked over to Thames River ready to jump and drown himself to death, but he came back to his senses and dragged himself back to his house. And there he found in his study a letter from an old friend, Charles Jennens, asking Handel if he would put music into passages of the Bible that he has written out. It was a libretto based on the life of Christ, with 32 references taken entirely from King James Bible. But Handel didn’t read the document but simply tore Jennen’s letter up, put the candle stick out and tried to get some sleep. But he couldn’t sleep so struggled to get up from bed and with a candle, he opened the document and started his composition. He grew so absorbed in the work that he hardly left his room, never left his house, and sometimes even skipping meals. Within six days part one of the oratorio was complete. In nine days more he had finished the second part, and in another six days, part three. And the orchestration was completed in just two days. Remarkably, all 260 pages of manuscript were finished in just a total of 24 days. A friend who visited him as he was working on the music told a story of how he found Handel sobbing with intense emotion. Later, as Handel tried to describe what he had experienced, had quoted St. Paul, saying, “Whether I was in the body or out of my body when I wrote it I know not.” Handel’s title for the commissioned work was, simply, Messiah. The Messiah not only brought Handel back into the spotlight but made him well-loved by the London high-society once again.

Messiah premiered in Dublin on the 13th of April 1742, as a charitable event, and it raised 400 pounds freeing 142 men from debtor’s prison. A year later, Handel finally staged Messiah in London, but controversy coming from the Church of England continued to plague Handel. Yet the King of England attended the performance. As the first notes of the triumphant “Hallelujah Chorus” was heard, the king stood up and the entire audience as well as the orchestra stood too, following royal protocol.

Afterwards, Handel’s fortunes began to increase dramatically, he was able to pay off his debts, and his hard-won popularity remained until his death. Handel personally conducted more than thirty performances of Messiah. Many of these concerts Handel conducted it himself to benefits the Foundling Hospital, of which he was a major benefactor. The thousands of pounds raised from Handel’s performances of Messiah led one biographer to note, “Messiah has fed the hungry, clothed the naked, fostered the orphan … more than any other single musical production in this or any country.” Another wrote, “Perhaps the works of no other composer have so largely contributed to the relief of human suffering.”

Although Handel was born in Germany, he was granted a British citizenship in 1727, and was accorded the status of a classic composer even in his lifetime. Handel died on Good Saturday, 14th of April 1759 (though he expressed his desire to die on Good Friday). He passed away just eight days after his final performance. He died at 74, and his close friend James Smyth wrote, “He died as he lived–a good Christian, with a true sense of his duty to God and to man, and in perfect charity with all the world.” Handel was given full state honours, and buried at the Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey, with over 3,000 in attendance at his funeral. A statue at the Abbey was erected showing Handel holding the manuscript for the solo that opens part three of Messiah, “I know that my Redeemer liveth.” His music became a vital part of England’s national culture. To this very day, his oratorio, Messiah, remains steadfastly popular and still being performed on stage across the country and around the world.

Handel’s letter to his friend Charles Jennens giving specific instructions about the organ he wanted for his oratorio.

Handwritten notes of Dr Ken Connolly (one of Jared’s mentors), “The Story of Handel’s Messiah” (Psalm 40:2). He was a great teacher, preacher and friend. He practically introduced me to the ancient history of England when he took me and Jared on a heritage tour of the city when I first arrived in London. It was difficult to decipher what was written on this notes but I am in the process of writing it out and someday adding the text here. 🙂

I’ve read this book, “George Frideric Handel: A Music Lover’s Guide to His Life, His Faith & the Development of Messiah and His Other Oratorios.” and it is a great book not just about Handel’s music but also about his personal life with emphasis on his religion; how his upbringing as a Lutheran shaped his life and music career. One of the questions raised in the book was how a lot of modern historians find it inconceivable that Handel remained celibate all of his adult life, if not part of it, and therefore they question his sexuality. The author argues that people who were close to Handel, his friends — opera singers and other performers, saw no evidence in him of any discreet love affairs or relationships. They all confirmed that they saw nothing in him but a consistent Christian witness, moral and chaste, to the end. If Handel had any illicit affairs, the author argues, it would have gone out to the public and not remain a secret because he was a high-profile figure of London society. It was a well-documented and enjoyable book.

Note: Jimi Hendrix House Museum is pretty cool too, and I’ll do a separate review for that. We visited both the Handel & Hendrix House on the same day.