Charmed by The Lakeland: Ancient and Historic Landmarks (2/3)

William Wordsworth once said, “I do not know of any tract of country, in which, in so narrow a compass, may be found an equal variety in the influences of light and shadow upon the sublime and beautiful.” The English poet was, of course, referring to the Lake District National Park which he immortalised in his poetry. As mentioned in my previous post I was absolutely captivated by The Lakes. Unarguably, it is the best known part of Cumbria, but there is more to this county than the Lake District.  Cumbria is predominantly rural and considered one of England’s most outstanding areas of natural beauty. Our friend Kevin drove us around and we visited the towns of Kendal and Windermere and along the route were many places of interest including ancient castles, medieval abbeys, stone and slate villages, charming cottages, friendly tea shops and pubs reflecting past glories that tell the story of Cumbria.

Cumbria is predominantly rural and considered one of England’s most outstanding areas of natural beauty. Our friend Kevin drove us around and we visited the towns of Kendal and Windermere and along the route were many places of interest including ancient castles, medieval abbeys, stone and slate villages, charming cottages, friendly tea shops and pubs reflecting past glories that tell the story of Cumbria.

The village of Crook, strung along the road between Bowness-on-Windermere and Kendal, is where our friend Kevin lives. (He lives in a charming Victorian cottage and I decided not to post any picture of his home to respect his privacy.) Crook has a lot of farms that date back as far as the 15th century, and we stayed in a historic farmhouse that’s been around for over 500 years.

The village of Crook, strung along the road between Bowness-on-Windermere and Kendal, is where our friend Kevin lives. (He lives in a charming Victorian cottage and I decided not to post any picture of his home to respect his privacy.) Crook has a lot of farms that date back as far as the 15th century, and we stayed in a historic farmhouse that’s been around for over 500 years.

The narrow winding lanes with drystone walls that match with the cottages on either side of the road, each possessing their own character, is one of the distinctive attributes of the Cumbrian landscape.

The narrow winding lanes with drystone walls that match with the cottages on either side of the road, each possessing their own character, is one of the distinctive attributes of the Cumbrian landscape.  Historic places of worship and ruined castles also abound. But one of the highlights of our trip was the visit to some of the most beautiful tiny village churches I’ve ever seen. It is worth mentioning though that in the UK there’s hundreds of churches (Catholics, Anglicans, Baptists, Methodists and other Christian denominations) that close its doors (more often converted into flats/houses or worst yet, a mosque) every year simply because the old parish system is no longer sustainable as congregation numbers dwindle. At churches in many rural areas, Sunday worshippers are in single figures. Parish churches are found throughout England and other parts of the UK, and have always been important features of the landscape. But gone are the days when the church was a major focus of life for the parishioners, much less for the general populace.

Historic places of worship and ruined castles also abound. But one of the highlights of our trip was the visit to some of the most beautiful tiny village churches I’ve ever seen. It is worth mentioning though that in the UK there’s hundreds of churches (Catholics, Anglicans, Baptists, Methodists and other Christian denominations) that close its doors (more often converted into flats/houses or worst yet, a mosque) every year simply because the old parish system is no longer sustainable as congregation numbers dwindle. At churches in many rural areas, Sunday worshippers are in single figures. Parish churches are found throughout England and other parts of the UK, and have always been important features of the landscape. But gone are the days when the church was a major focus of life for the parishioners, much less for the general populace.

This building (above photo) is St. Catherine’s Church – Crook, built in 1882 but still retains a 14th century bell from an earlier church.

This building (above photo) is St. Catherine’s Church – Crook, built in 1882 but still retains a 14th century bell from an earlier church.  This tower is a remnant of the 14th century manor chapel for Crook Hall. (It was on a hilltop right behind Crook Hall Farmhouse.) It served the village people from the 16th to the end of the 19th century. The bell from this tower was transferred to St. Catherine’s Church in 1887. Most old parish churches in England possess towers, generally at the west end like St. Catherine’s.

This tower is a remnant of the 14th century manor chapel for Crook Hall. (It was on a hilltop right behind Crook Hall Farmhouse.) It served the village people from the 16th to the end of the 19th century. The bell from this tower was transferred to St. Catherine’s Church in 1887. Most old parish churches in England possess towers, generally at the west end like St. Catherine’s.

St. Catherine’s has a remarkable hammer-beam roof. The day we visited it was all decorated in preparation for the Queen’s 90th birthday celebration.

St. Catherine’s has a remarkable hammer-beam roof. The day we visited it was all decorated in preparation for the Queen’s 90th birthday celebration.

I love the door and the hammer-beam roof.

I love the door and the hammer-beam roof.

This door has beautiful ironwork details. (If I ever build a house, anywhere in the world, I’d have a door similar to this. 😉 )

This door has beautiful ironwork details. (If I ever build a house, anywhere in the world, I’d have a door similar to this. 😉 )

I like antiques; old, weathered, beaten and battered objects, and this door of an old church in Mirfield is a fine example of that ‘old-world’ stuff I am very fond of. My fascination with old churches (especially its doors) is a result of my love of history. There is a beauty to these old churches that doesn’t exist in modern churches.

I like antiques; old, weathered, beaten and battered objects, and this door of an old church in Mirfield is a fine example of that ‘old-world’ stuff I am very fond of. My fascination with old churches (especially its doors) is a result of my love of history. There is a beauty to these old churches that doesn’t exist in modern churches.  Old parish churches (like St. Catherine’s) have a graveyard as well. Historically the most common use of churchyards was as a graveyard or place of burial. In England graveyards were usually established at the same time as the building of the church (which can date as far back as the 6th to 14th centuries) and were often used by poor families who could not afford to be buried inside or beneath the place of worship itself.

Old parish churches (like St. Catherine’s) have a graveyard as well. Historically the most common use of churchyards was as a graveyard or place of burial. In England graveyards were usually established at the same time as the building of the church (which can date as far back as the 6th to 14th centuries) and were often used by poor families who could not afford to be buried inside or beneath the place of worship itself.

We also visited this little chapel, St. Anthony’s Church in Cartmel Fell, a parish and tiny village of about 300 population. Nestled in a delightful location in the Winster valley between Whitbarrow Scar and the southern tip of Windermere, this building was erected in 1504, and externally it has very little architectural significance. Its walls are made of local limestone bricks, the windows are square-headed and the tower has a rather nondescript character but the interior is amazingly captivating. Jared and I obviously had the pleasure of exploring this church, thanks to Kevin. He works for the local council and has access to all of these historic landmarks.

This is the path to St. Anthony’s Church and its graveyard, on the right side is a Parish Hall. The lychgate (a roofed gateway to a churchyard, formerly used at burials for sheltering a coffin until the clergyman’s arrival) was built to commemorate the fallen during the Second World War. Beside the path from lychgate there’s also a memorial to the parishioners who served in the First World War.

This is the path to St. Anthony’s Church and its graveyard, on the right side is a Parish Hall. The lychgate (a roofed gateway to a churchyard, formerly used at burials for sheltering a coffin until the clergyman’s arrival) was built to commemorate the fallen during the Second World War. Beside the path from lychgate there’s also a memorial to the parishioners who served in the First World War.

My great interest of the building lies in its interior’s woodwork and ancient stained glass windows.

The boxed pew on the left side (above picture) is known as the Cowmire Hall pew, and on the right side is the Burblethwaite Hall pew. (Cowmire Hall is a country house originally built as a tower house in the early 16th century, and Burblethwaite, is the only estate in the village, a manor owned by a family surnamed Knipe who claimed to have built this chapel in 1504.) Both boxed pews have wooden ornate carvings on the canopies. Just behind the Burblethwaite Hall pew, on the right, is the canopied three decker pulpit.

The boxed pew on the left side (above picture) is known as the Cowmire Hall pew, and on the right side is the Burblethwaite Hall pew. (Cowmire Hall is a country house originally built as a tower house in the early 16th century, and Burblethwaite, is the only estate in the village, a manor owned by a family surnamed Knipe who claimed to have built this chapel in 1504.) Both boxed pews have wooden ornate carvings on the canopies. Just behind the Burblethwaite Hall pew, on the right, is the canopied three decker pulpit.

This three decker pulpit dates back to 16th century, one of the original elements of the building.

This three decker pulpit dates back to 16th century, one of the original elements of the building.

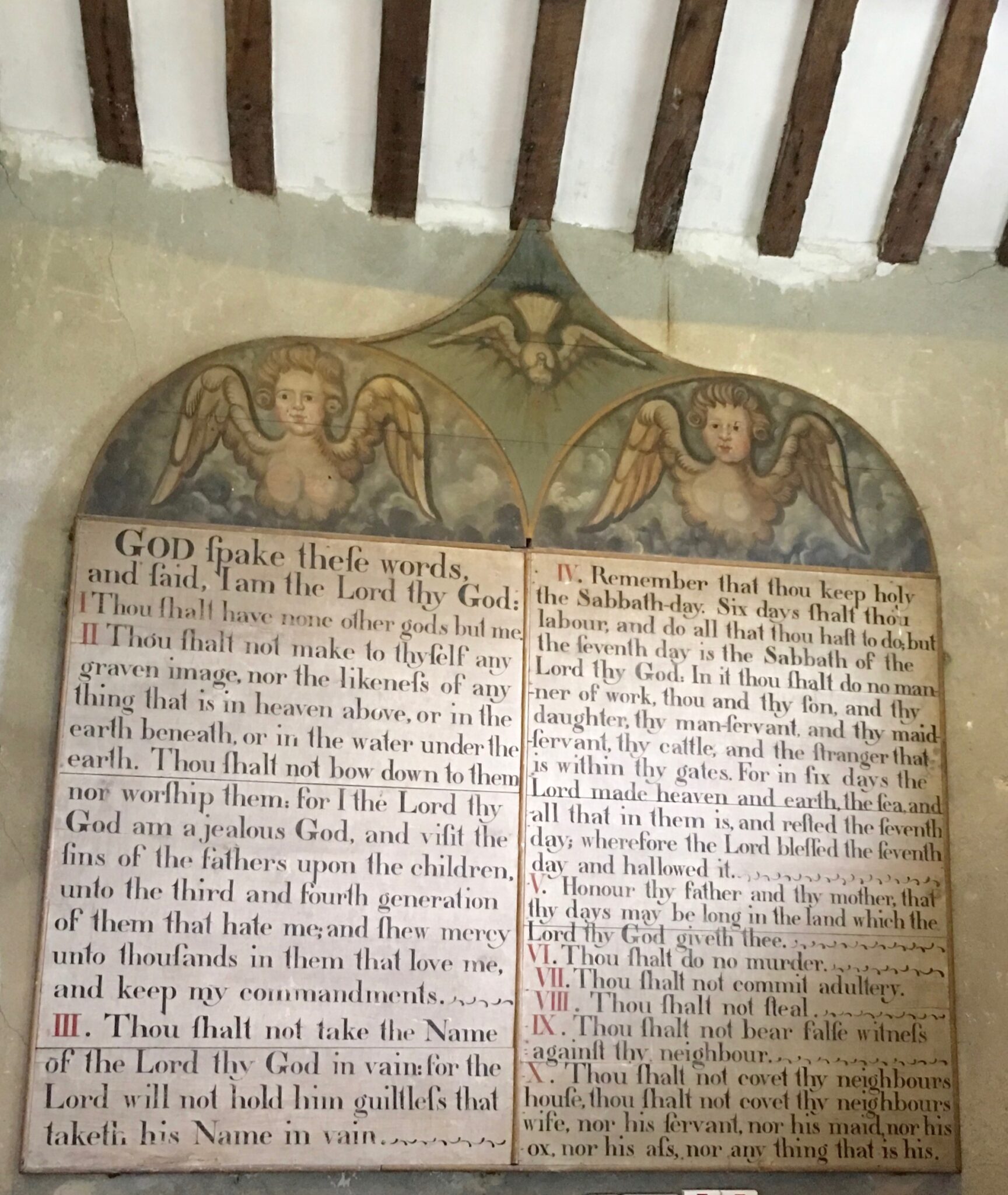

This is the only church I’ve seen that has boxed pews so I asked Kevin about it and he said that this is quite a unique feature of a tiny village church reserved for the VIPs. I recall from my reading years ago (on the history of Anglican Church) that the origin of English parish-churches was, generally speaking, the construction of a chapel by the feudal lord of a manor on his own property, for the benefit of his own family and his tenants. So the boxed pews, I assume, would have been reserved for the Lord of the Manor and his family. But after the Reformation when feudal dignity faded away, and the property of ancient families began to be transferred to other hands, these boxed pews would have been allocated to influential families in the village and/or the most generous benefactors of the parish church. I can only imagine that in the olden days the members of the landed gentry were always competing to give a substantial donation to secure their place on the most luxurious accommodation for sitting. 😉  This church was built in the late medieval/early modern period so this huge stone tablet was inscribed with Ten Commandments in an old style printing: “God fpake thefe words, and faid, I am the Lord thy God . . .” (According to Webster Dictionary: In genuine old-style printing it can appear that the letter f is used in place of the letter s. However, it is not the letter f, but a long form of the letter s (derived from handwriting styles), which looks very similar to f but does not have a complete cross-bar. It is not used at the ends of words, and in words where there is a double s, it is sometimes paired with a short s (which results in a compound letter like the German double-s (or `sz’) symbol `ß’). It fell out of fashion with printers rather suddenly in about 1780.)

This church was built in the late medieval/early modern period so this huge stone tablet was inscribed with Ten Commandments in an old style printing: “God fpake thefe words, and faid, I am the Lord thy God . . .” (According to Webster Dictionary: In genuine old-style printing it can appear that the letter f is used in place of the letter s. However, it is not the letter f, but a long form of the letter s (derived from handwriting styles), which looks very similar to f but does not have a complete cross-bar. It is not used at the ends of words, and in words where there is a double s, it is sometimes paired with a short s (which results in a compound letter like the German double-s (or `sz’) symbol `ß’). It fell out of fashion with printers rather suddenly in about 1780.)

The altar with exquisite stained glass windows. There’s also two large stone tablets with prayers inscribed.

The altar with exquisite stained glass windows. There’s also two large stone tablets with prayers inscribed.

The stained glass is 15th century and comes from Cartmel Priory, the parish church of Cartmel, founded in 1190 by the 1st Earl of Pembroke.

The stained glass is 15th century and comes from Cartmel Priory, the parish church of Cartmel, founded in 1190 by the 1st Earl of Pembroke.

There is a small pipe organ at the northwest end of the nave. Most medieval churches were rebuilt and modified on a number of occasions but for this particular church, the fabric of the building, interior as well as exterior, is still easily visible.

There is a small pipe organ at the northwest end of the nave. Most medieval churches were rebuilt and modified on a number of occasions but for this particular church, the fabric of the building, interior as well as exterior, is still easily visible.

This cozy little nook under the tower is a fine example of the medieval architecture. Amazingly, the chapel does not have the usual old church smell, it was very clean and not dusty at all, and is obviously well-taken care of by the parishioners. Just like St. Catherine’s, this is also an Anglican Church, though it was originally built as a Roman Catholic Church. The Brits can blame King Henry VIII for that! 😉

This cozy little nook under the tower is a fine example of the medieval architecture. Amazingly, the chapel does not have the usual old church smell, it was very clean and not dusty at all, and is obviously well-taken care of by the parishioners. Just like St. Catherine’s, this is also an Anglican Church, though it was originally built as a Roman Catholic Church. The Brits can blame King Henry VIII for that! 😉

There’s just something mesmerising about these old church buildings, about the bygone eras. I certainly look forward to visiting Cumbria again in the near future and seeing more of the historic landmarks.